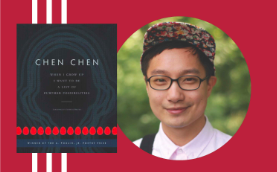

Assistant Managing Editor Audrey Bowers had a chance to interview poet Chen Chen, who will be visiting Ball State for the In Print Fesitval on March 20 and 21. Come hear Chen Chen read from his debut poetry collection, When I Grow Up I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities on Wednesday, March 20 and talk about his experiences writing and publishing his first book on Thursday, March 21. Both events will be at 7:30PM in AJ 175.

Assistant Managing Editor Audrey Bowers had a chance to interview poet Chen Chen, who will be visiting Ball State for the In Print Fesitval on March 20 and 21. Come hear Chen Chen read from his debut poetry collection, When I Grow Up I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities on Wednesday, March 20 and talk about his experiences writing and publishing his first book on Thursday, March 21. Both events will be at 7:30PM in AJ 175.

Check out Managing Editor Kimmi Beard’s interview with poet and editor Allison Joseph; you can find interviews with essayist Dustin Parsons and fiction writer Maria Romasco Moore, and excerpts of their work, in the Spring 2019 issue of The Broken Plate.

______

Audrey Bowers: One of the first poems I read of yours was “Poem in Nosy Mouthfuls” and it resonated with me as a queer writer. I’ve noticed that a lot of your work considers similar subject matter, often about your various identities and how they overlap. How do you continue to find a unique perspective on questions of identity in your work?

Chen Chen: First, I try not to put too much pressure on myself to find some completely new angle on the subjects that obsess me. Sometimes, I worry about returning to the same subjects over and over, but then I consider how seemingly slight changes in perspective can lead to fresh (and mammoth!) discoveries within those subjects. After all, this present moment is a fresh and different one from every other moment that’s come before.

So, for example, writing about being queer right now, in the emotional and physical conditions I’m inhabiting, is going to be different from how I previously approached the topic—if I’m paying close enough attention and also being honest. Instead of attempting to match a fixed image that I already have in my head, I have to open myself up to the topic as it is speaking to me, now. It’s a listening process, a practice of receptivity. I try my best to put aside preconceived notions and clever plans. My aim is to enter a living stream, not to control or master the landscape. Sometimes I fail with this aim, but then I try to listen to that failure, see if there’s another trajectory available in the mistakes themselves.

AB: Many writers, including myself, struggle with self-doubt, frustration, and lack of inspiration. How do you work around or through those common barriers?

CC: I contend with those issues all the time. I’m indebted to Kimiko Hahn who, at a Kundiman Writers’ Retreat, used the term “low stakes writing” and encouraged us all to stop overthinking. It’s not that I believe “overthinking” or just “thinking” is the ultimate enemy of creativity. I’m often reinvigorated by theory and critical texts (I keep thinking of Sara Ahmed’s beautiful book, Living a Feminist Life, for instance). But there’s a certain type of overthinking that tends to be a roadblock—a perfectionist mindset.

So, lowering the stakes at the beginning is a great way to sidestep the self-doubt. What I’m writing doesn’t have to be a poem, not yet. It can just be a series of observations. A set of images. Notes. A scribble or two. I also don’t need to be super inspired to start writing this way. It can be completely mundane, even boring. Sometimes the boring thing can lead to what I haven’t considered before, need to consider differently. Again, I try to stay open, rather than attached to some big idea. Eventually I accumulate all these wild bits, glittery debris, and they start to feel like they could belong together. Or through a scrap of a memory, I stumble into an inviting strangeness, a larger question; and I just keep writing, writing.

And when it’s not going so well, at least I’ve given myself the time to reflect and, if I’m writing by hand, I’ll have gotten to use a ferociously pink pen or a fabulously sharp pencil. So, the bad writing still looks kind of great on the page. (That nice appearance should not be confused with quality writing, but yes, wonderful writing implements and wonderful stationary make me happy.)

AB: We’ve talked a lot in our class about how publishers often prioritize the voices of white, middle class, heterosexual writers. Have you had to work against these biases in finding homes for your work? What can editors do to ensure they are supporting underrepresented voices?

CC: I don’t know which of the rejections I’ve received have had to do with these kinds of biases, though I suspect some of them have. What’s most important is to support black editors and editors of color, queer and trans editors, editors with disabilities, working class editors, and editors whose identities and experiences are “othered” in more than one of these ways. And support means reading the journals these editors run, sending work to them, donating to their fundraising, sharing and discussing what they publish, attending reading events they host. When I was younger, I didn’t think I could be an editor of a literary journal. I thought that was something only older people, usually white and male, were in charge of—they were usually the people in charge of so much else.

I am queer and Asian American. I am an immigrant. I grew up in a bilingual household—really, a trilingual one, as my parents spoke English, Mandarin Chinese, and Amoy Hokkien (sometimes referred to as a dialect; sometimes referred to as a language). I grew up in Western Massachusetts and also the Boston area. I’ve lived in Upstate New York and West Texas. I’ve studied French and Russian. I’m most drawn to poems that mix the overtly political with the uncompromisingly emotional, but I like a wide range of work. All of these experiences, identities, histories, and tongues shape how I read, what I’m seeking to publish and support as an editor of Underblong. And I work with a wonderful team—Sam Herschel Wein, Mag Gabbert, E Yeon Chang, and Emma William-Margaret Rebholz aka Billy. These are fellow writers and readers who also bring their experiences, identities, histories, tongues. Their imaginations. Their knowledges.

My sense is that it tends to be the smaller and primarily online journals that have teams like this and a more collaborative process for selecting work to publish. The big literary journals that have been around for ages need (a lot) more pushing. I don’t think they really change all that much with just the main editor position changing from someone less “progressive” to more, or from a white, middle class, heterosexual man to a person of a marginalized subject position. They have to change on a structural level, where more editors’ voices really matter (not just guest editors for special issues). I also think there should be term limits for editorships at these big deal journals (that have all the funding). Critiquing these institutions and amplifying others who are offering important critiques is part of what I can contribute. At the same time, I will keep investing in and uplifting the smaller journals and the marginalized editors who are doing so much labor to create better spaces for so many writers.

AB: I know that you write both poetry and prose. What does the process of writing in two different (yet somewhat similar) genres/forms typically look like for you?

CC: I find poetry more fun to write than prose, but I think that’s largely because I haven’t explored and experimented enough in the latter. What’s so fun to me about poetry is the linguistic play, the sonic play, and also the visual adventure that can happen on the page. I know all of that is possible in prose; it’s just that poetry tends to make all of those elements more salient or dominant. For example, if I start writing in couplets, I’m immediately considering what this pattern of two-line stanzas does for the subject I’m engaging—the kind of juxtapositions I can create, the kind of tensions.

Paragraphs feel more static to me. So blocky. Though I love reading prose poems and have been writing more of those myself. I don’t know. Maybe I should try writing an essay as a lineated poem first, then try it out in paragraphs. I’m drawn to the lyric essay because of all the fragmentation and white space; there seems to be more room for play. I also feel resistant to constructing/portraying a very consistent self on the page. Poetry feels like a larger container, to me, for contradiction and unresolvedness. But again, I think these feelings come from my lack of practice and lack of imagination in (longform) prose forms. I need to play around more, for the play in prose to become more apparent, more available to me. I want my prose to become really mine; to live as that larger container, larger room I can move around in, knocking over jars, banging my knee against a bedframe, putting cat stickers up on the sides of windows.

AB: I am a huge fan of your social media presence, specifically Twitter. How does your writing voice vary between your tweets and your more traditional forms of writing?

CC: Thank you! I’m glad my Twitter presence is a good one, haha. My tweets tend to be very informal and spontaneous. They can also be a place where I think through things seriously. Lately, I don’t want to spend too much time on them, because there’s only so much time in a day and I just feel better when I’m not on social media too much. That said, I do enjoy the community that can form online. I love learning about exciting books I need to read and connecting with fellow teachers of creative writing. And I do try my best to take care with how I comment on more serious subjects and not position myself as any sort of expert on things I’m just not an expert on.

Sometimes, tweets can lead to more traditional forms of writing. A line that I first tweeted has made its way into a poem here and there. Also, I’ve been sharing writing prompts on Twitter for a while and some of those made their way into a craft chapbook that Sundress Publications will be releasing soon—You MUST Use the Word Smoothie: a Craft Essay in 50 Writing Prompts. So, tweeting can sometimes be a form of brainstorming, or early drafting/pre-drafting. I’m grateful to fellow writers on Twitter who’ve responded and encouraged and helped hone various lines and ideas.

And thank you for all these questions, this opportunity to reflect!

____

Chen Chen is the author of When I Grow Up I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities (BOA Editions, 2017), which was longlisted for the National Book Award and won the Thom Gunn Award, among other honors. The recipient of fellowships from Kundiman and the National Endowment for the Arts, Chen’s work appears in many publications, including Poem-a-Day, The Best American Poetry, and The Best American Nonrequired Reading. He holds an MFA from Syracuse University and a PhD from Texas Tech University. Currently he teaches at Brandeis University as the Jacob Ziskind Poet-in-Residence. With his best friend, Sam Herschel Wein, he co-runs the journal, Underblong.

Audrey Bowers is a senior creative writing major at Ball State University. When they aren’t writing poems, you can find them editing Brave Voices magazine.